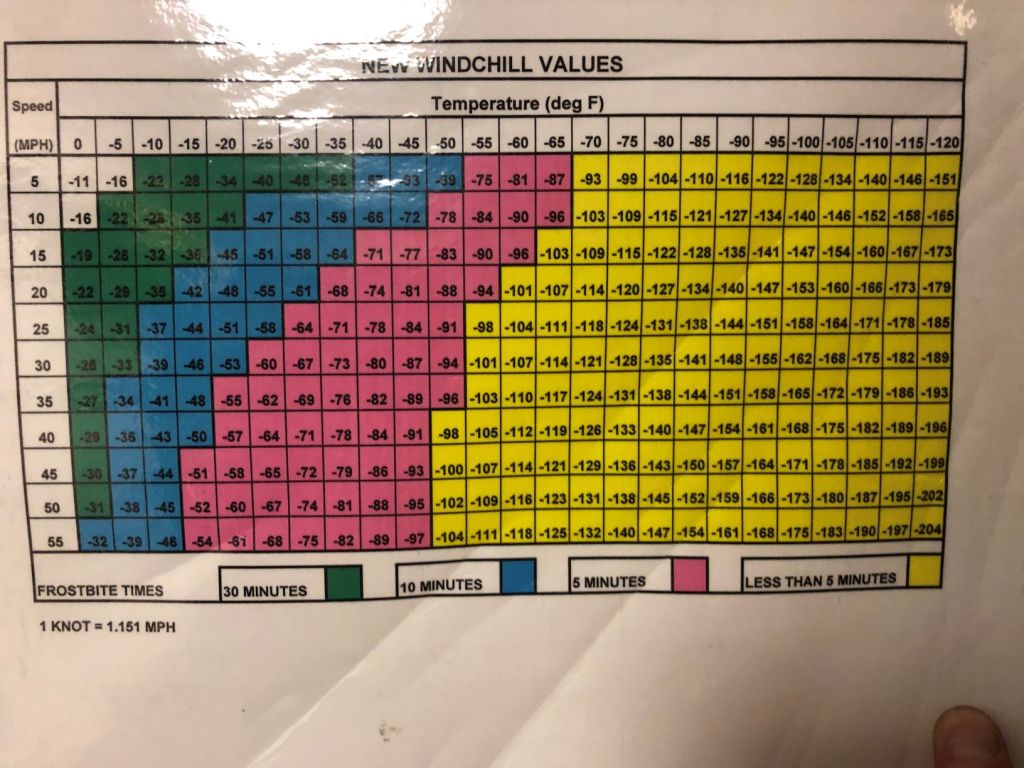

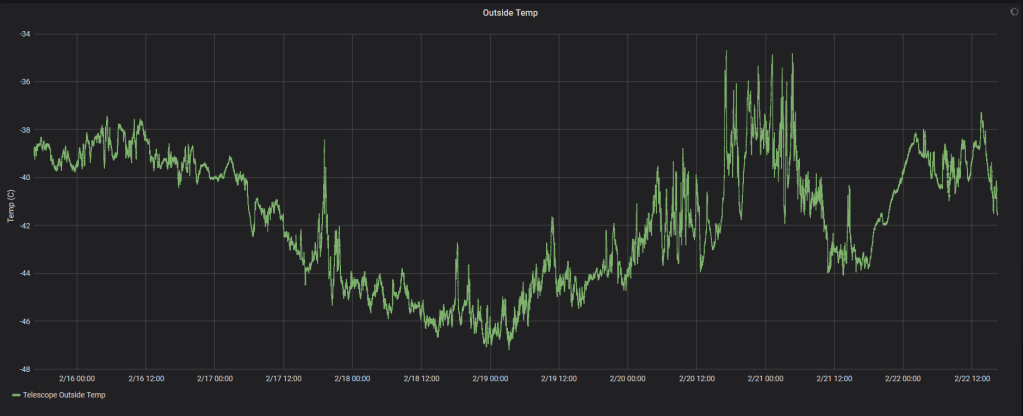

Weather: Fluctuating almost daily between overcast and blowing snow, and cold and clear. Temperatures steadily around -65F with windchill hovering just above -100F. There is only 1 week left with the sun above the horizon.

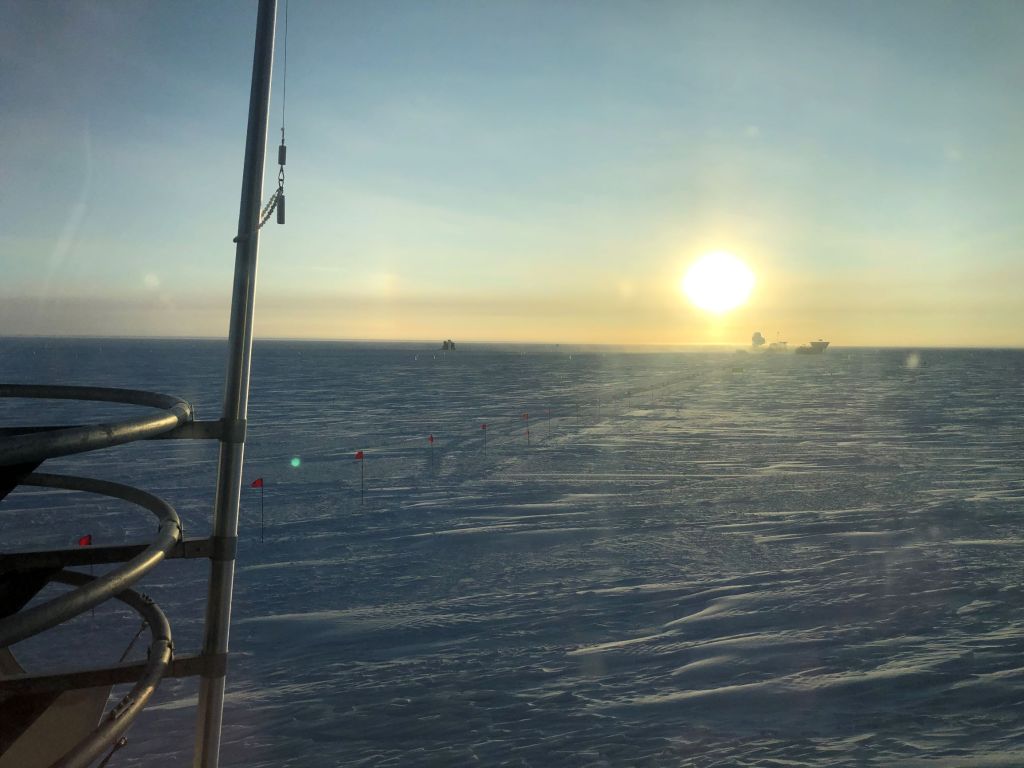

As the sun gets lower on the horizon we can start to see some familiar sunset colors in the sky… that is, of course, when it’s not completely grey and flat-white outside. With the weather flip-flopping between near white outs and beautifully clear like the photo above, we all hold our breath and cross our fingers for a clear sunset. Nearly everyone on station has begun taking timelapses, either outside in heated boxes, or inside against windows.

Things ain’t all pretty, though. We still have some dirty jobs to do, including greasing the gears of the telescope. Soon enough it will be dark and we’ll have to use red headlamps to see our hands in front of our faces… but for now, greasing in the afternoon sunlight isn’t so bad!

Another fun thing about winter, is that there are no more outhouses. There is too much blowing snow (and will be no Sun, so the solar huts are not effective at staying warm), so the outhouses get put away in late February until next summer. Now, we have ‘The Little Boiler’s Room’ — which is actually the boiler room… with a 55 gallon drum, well two 55 gallon drums, but don’t use the 2nd one, that’s full of glycol for the heating loop!

Now for a new segment on my blog:

SCIENCE SUNDAY!

I’ll try to post some sciencey thing here each week… you know, because I do science, and I’m doing science at the South Pole, or at least that’s what I tell myself.

Today’s science: Why SPT3G is such a special CMB experiment.

The Cosmic Microwave Background is the remnant heat from the early universe. When the universe was young it was much smaller, and thus also much hotter — think of a pressure cooker; increasing the pressure makes it hot.

Since then, it has expanded and cooled to 2.7 degrees Kelvin above absolute zero (that’s really cold! in Freedom Units, that’s -454F). The heat has been streaming across the universe from the very beginning, for 13 billion years, until it finally hits our detectors. This means that when we measure the photons, we are also looking back in time at what the universe looked like 13 billion years ago. It also means that these photons who traveled to us all the way from the hot, early universe tell us about the structure in the universe. For example if a photon is traveling on it’s merry way and galaxy happened to have formed since the beginning of the universe (and they have, thankfully!), then that photon could run into the galaxy and get absorbed, or even interact with some hot, ionized gas within the galaxy and receive a boost in energy as it interacts.

Indeed, this is why the CMB is such a rich data set for studying the universe, because it not only tells us what the early universe was like, but also what our universe is like along the way. What makes the South Pole Telescope so special is the size of the primary dish. The 10m dish means that we have high angular resolution; i.e. that we can see things that appear very small on the sky such as galaxies or even distant clusters of galaxies.

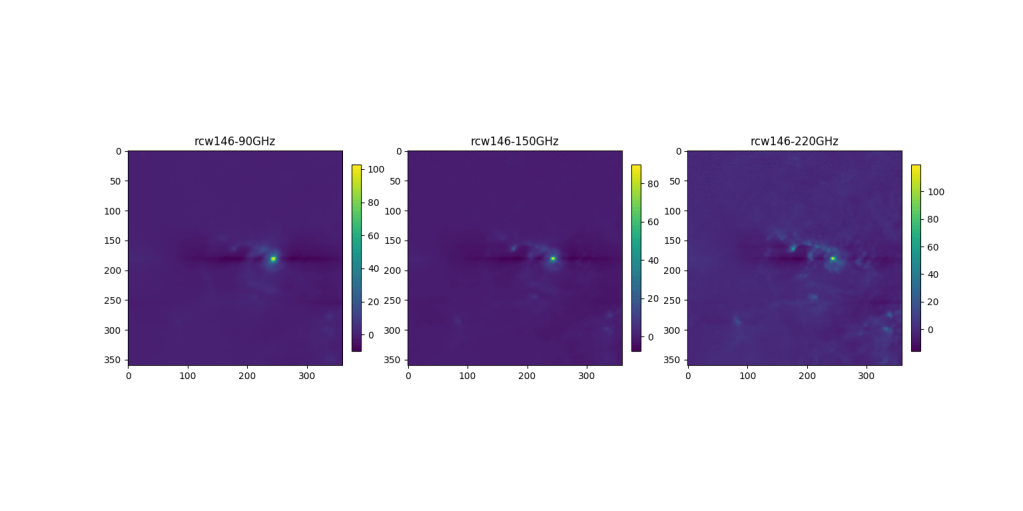

Of course, SPT doesn’t see in the optical wavelengths because we want to observe the CMB, whose photons have cooled over 13 billion years to 2.7K. The majority of the photons now have a wavelength around 1mm long! Compare that to optical photons whose wavelength is a few hundred thousand times smaller! So when we ‘see’ these objects (galaxy clusters, dusty galaxies, active galactic nuclei) we’re seeing them in the microwaves. Some objects produce their own microwaves, such as active galactic nuclei (AGN) where high-energy electromagnetic jets are shot out of their central black holes, causing radiation in the mm-waves and causing warm gasses to emit in the mm waves. Other objects, like massive clusters of galaxies, actually effect the CMB photons as they travel on their way to us.

One such effect, called the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (SZ) effect occurs when low-energy CMB photons pass through galaxy clusters and receive a net boost in energy due to interactions with hot electrons in the cluster.

Another effect, called the Sachs-Wolfe effect causes photons passing through a massive gravity well (caused, for example, by a massive cluster of galaxies) to gain or lose energy. This can only happen if the gravity well has different depths between when the photon enters and when the photon leaves the well. One such mechanism for this is inflation; since these clusters of galaxies are so large, it takes millions of years for a photon to travel through the gravity well, during such a time, the universe is expanding, and thus the gravity well is getting shallower and shallower, and thus the exiting photon doesn’t have to climb out of such a large gravity well; it then gains some energy compared to what it was before entering the well.

These and other effects change the energy spectrum of the CMB photons as they arrive at Earth. By measuring the spectrum of energies of a certain source, one can gain a better understanding of the physical mechanisms at play.

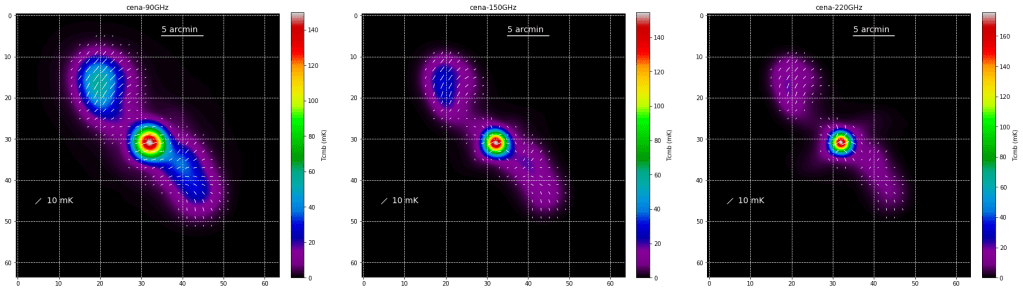

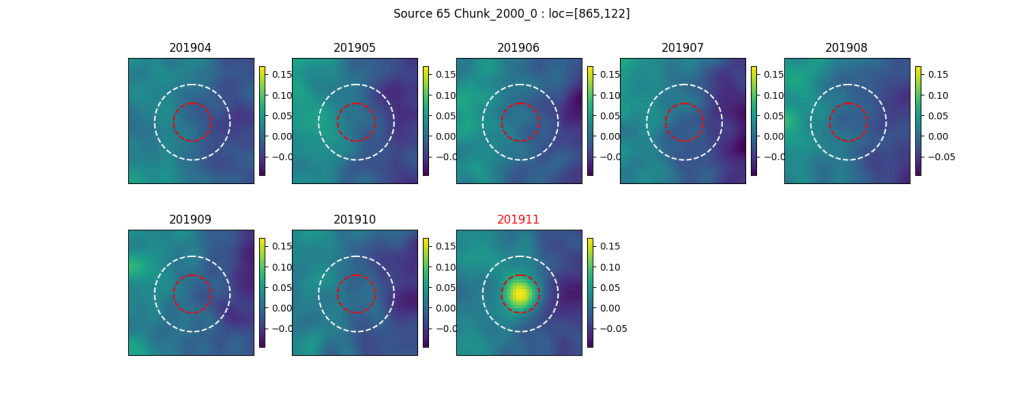

Below is a small zoomed in section of a heavily filtered SPT3G CMB map. The color scale is in micro-Kelvin (1/1,000,000th of a Kelvin), and shows the departure from average. The larger scale structure is caused by filtering our maps in the scan direction and shouldn’t be thought of as physical structure, but the small-scale structure that look like red or blue dots are indeed physical. The red dots are objects with higher-than-average signal (from things like dusty galaxies or active galactic nuclei which are generating their own source of mm-wave signals), the big blue dot near the middle of the image is a large galaxy cluster which has boosted the CMB photon energy up out of this frequency band. The image is about 4deg x 3deg on the sky, and you can see tens of sources in the map (even with this out-of-the-box filtering). Our full survey size is about 100x this area.

So why is SPT3G so special? We can not only survey 1500 sq degrees of CMB , but we can get high-resolution measurements of these ‘foreground sources’, which in turn effect the measured energy spectrum of the CMB photons. Understanding these foreground sources is instrumental to understanding the exact signal contained in those early-universe photons before they interact with all of the material along their way to us.

Whew! Hopefully that made some sense!

Next week I might talk about something completely different – the Event Horizon Telescope. Stay tuned!